A couple of years ago, my family and I went on a camping trip down to the United States (back when such a thing was possible).

As one does, we visited some of the iconic landmarks along the way, one of which was Mount Rushmore. The first thing that surprised me was the size; it was a lot bigger in my head.

But what really caught my eye was the scree of broken stones down below.

A view of the scree below the faces.

A view of the scree below the faces.

That pile of rock represented 410,000 tonnes of material taken off the mountainside, removed by 400 men hanging from harnesses and cables, using dynamite, jackhammers, and chisels for 14 years to shape it.

That rubble at the bottom is a symbol of all that hard work.

I had a much smaller pile after last week’s essay, but it was rubble nonetheless.

The final word count of “A Tool Against Writer’s Block” came out to 1349 words. This includes the introduction that I tagged to the top of the newsletter and the short postscript asking for your support.

I probably put in ten hours of work, shaping and reshaping those words.

Along with all of this, there are several other documents filled with rejected versions. These might be scraps that didn’t work or lines that I hoped to reintegrate later. I also dug through some older abandoned essays, and pilfered them for material, then unceremoniously dumped when they were no longer of value.

This whole process left me with seven discarded versions, which added up to 8,175 words. That means I had almost six times the amount of material in my trash pile than I had for the completed essay.

That’s a lot of time and energy that most people will never be aware of.

When I go into schools to talk about writing (back when such a thing was possible), I liked to ask students how many times they edit their work. I know this is a pain point for teachers because most kids only do one or two passes.

Then I’d share with them the dozens of edits we did before sending it to our editor, and then, I’d ask how many corrections our editor would make. They’d always guess too low and as their numbers slowly increased into the thousands, I’d eventually get the one kid who’d say one million, and I’d have to scale them back to the tens of thousands of edits we’d make.

I think this is important for any young writer to understand because often we undervalue the importance of editing and rewriting.

Except, it’s a tough lesson to learn, and even as we grow into writers with stories and books under our belts, we needed to be reminded of the rubble left behind.

When we look at those sculptures on the mountain, the statues in the museum, or the award-winning books on the shelves, we admire how finely crafted they are, but forget the work involved.

This is dangerous thinking because it sets an unrealistic expectation.

We think that we can never achieve such greatness or perfection, and we forget about all the effort required to get there: the abandoned words, the failed phrasing, and the excised scenes, chapters, and storylines.

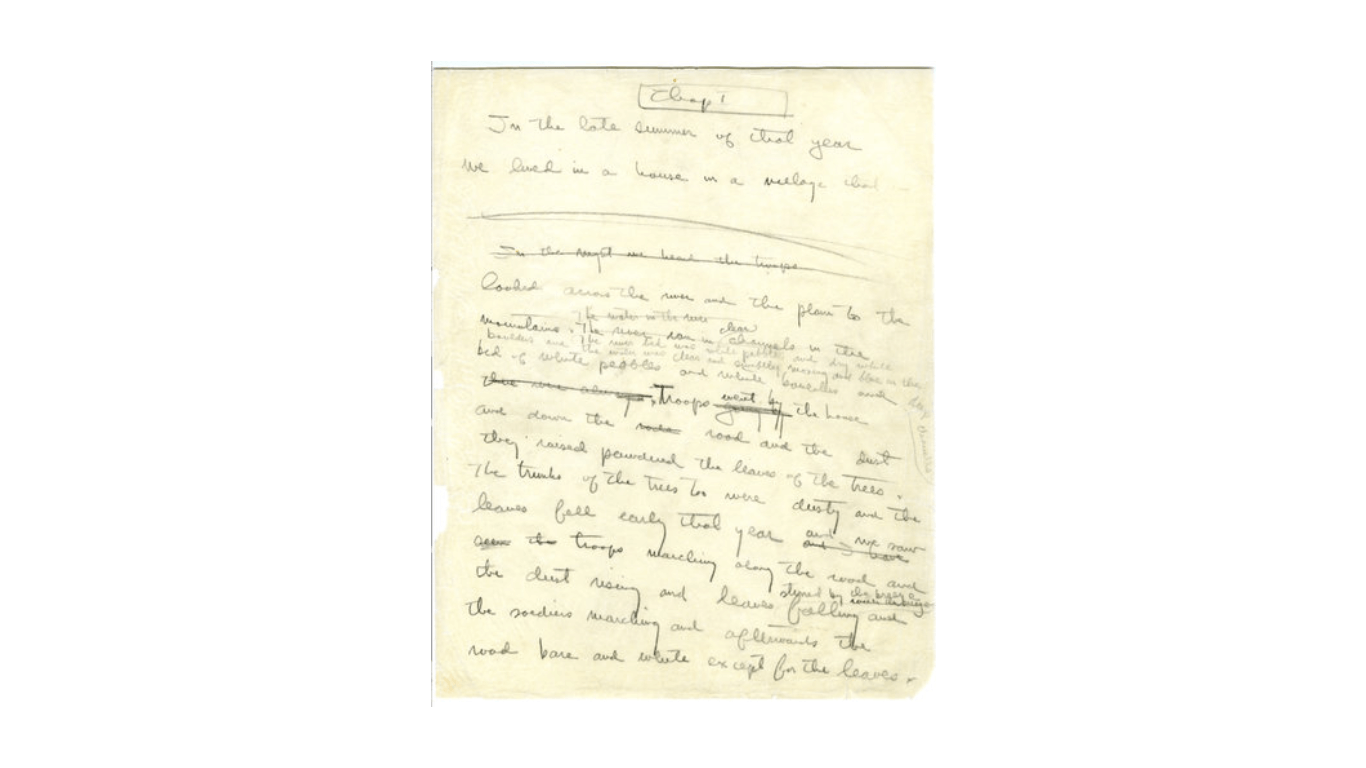

A page from Ernest Hemingway’s draft of “A Farewell to Arms.”

A page from Ernest Hemingway’s draft of “A Farewell to Arms.”

Yet, we don’t stop there.

We also forget the time spent building the craft. We forget about the painful first stories, the failed drafts, the pile of rejections, and the hard lessons learned.

We only let ourselves see the final book and put blinders on to the time and effort spent getting there.

Nearly a year and a half ago, I remember seeing someone on Twitter ask, “Why is writing so hard?” and the answer in my head was, “Why do you think it should be easy?”

Writing can be a messy and hard business (not the kind where you hang off the side of a mountain and chisel it with sweat and dynamite, but still hard). So, to better ourselves at the craft of writing, we need to move into that headspace.

We need to accept we’ll make a mess and that our first (or second or fifth or twelfth) draft is not our final one.

We need to remember that the great writers before us didn’t have a perfect copy the first time either.

We need to allow ourselves to make mistakes and go down tangents that may not work, only because that’s how we discover what does work.

And most importantly, we must accept that we need to write badly at first to get better.

So, the next time you are struggling and thinking your writing looks and sounds like shit, then remind yourself this: it probably is shit, and that’s okay.

It means that you are aware of it and can improve it through the use of craft. It means that you can chip away here, blast away there, and slowly shape it (and yourself) into something better. Best of all, it also means that when you face a similar problem next time, you’ll now have the skills and knowledge to address it.

Like Mount Rushmore, your books are not just the face of your writing, but what you’ve left behind—the words written, the lessons learned, the time spent doing the work—and that is the real effort that shaped and defined you as an artist.